Historical Perspective

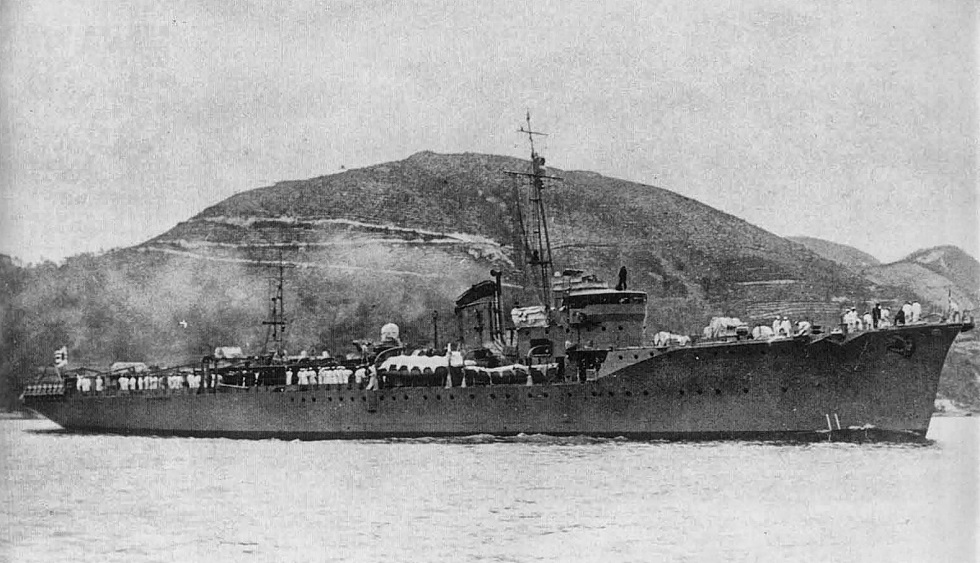

Giving its name to that class of ship, the Imperial Japanese Navy Minelayer Hatsutaka was completed in October 1939. Built by Harima and Co. and measuring 90.9 metres in length with a beam of 11.3 metres, Hatsutaka displaced 1608 tonnes. She was equipped with three boilers delivering 6000 hp, giving the ship a maximum cruising speed of 20 knots.

The Hatsutaka class, were dual-purpose minelayers and net-tenders with a capacity of up to 360 mines. At the time of building, HIJMS Hatsutaka was armed with four 40mm guns and an additional four 25mm anti-aircraft guns.

Later in WW2, as the Japanese became desperate to counter the increasingly effective Allied submarine offensive they converted HIJMS Hatsutaka into an escort. Operating throughout the Gulf of Thailand and Malaysia, Hatsutaka became a familiar enemy of US submarines, fiercely defending Japanese Marus transporting raw materials to fuel the war machine.

On May 3rd 1945, Japanese Naval records show that the Hatsutaka attacked a submarine in the southern Gulf of Thailand, dropping depth charges on the submerged vessel at 30 fathoms. People believe that this is the Baleo Class submarine USS Lagarto [SS-371]. All 86 men on the USS Lagarto were lost. This sub was (identified) and found in the Gulf of Thailand, by Thailand- based tech dive operator Jamie McCleod aboard his MV Trident.

Commanding Officer of the USS Lagarto, Commander Latta had previously made seven patrols as the CO of USS Narwhal II (SS-167). Each of these was designated successful for the award of combat insignia, a record unsurpassed in the Submarine Force.

USS Hawksbill [SS-366] Commanding Officer, Lt. Cmdr. F. W. Scanland, Jr. was a close friend of Commander Latta. Stationed in peninsular Malaysia, he swore to avenge the loss of the Lagarto.

This excerpt is from the Official History of the USS Hawksbill [http://usshawkbill.com].

“Continued westward and at two o’clock in the morning, 16 May, commenced patrolling in shallow water seven miles off the Malay coast, just north of Pulo Tenggol, Malaya, scene of much of Hawksbill’s later actions.

Within two hours after arrival on station, and 2 hours before dawn, Hawksbill contacted an unidentified target running south along the coast. Within an hour after contact, after closing to get at the target before he could enter a mined area behind Pulo Tenggol, Hawksbill had fired six torpedoes from the forward nest for two hits. Range was 2600 yards. Target stopped and opened up with a barrage of four-inch and automatic weapons fire which lasted off and on until seven o’clock in the morning. Hawksbill had hurt the target, but it was still afloat, and its’ gunfire held Hawksbill off during darkness.

Pulling clear until dawn, Hawksbill submerged and started back in, closing sufficiently to identify the target as a sleek, fast mine layer of the Hatsutaka Class. A small sea truck of about 400 tons was towing it slowly to the beach, stern first. At extreme range of 4650 yards, Hawksbill fired a second salvo of three torpedoes at this target. Sighting the wakes, Hatsutaka opened fire with everything he had in an effort to detonate the torpedoes. To no avail, however, for one broke him in two with a terrific explosion amidships.”

Davy Jones Locker Dive Expedition: March 28th 2008, Eastern Peninsular Malaysia

After researching war reports and cross referencing this data against local knowledge, we determined the likely location of HIJMS Hatsutaka. Malaysian fishermen were aware of a large wreck in their waters, agreeing that the time period was correct. However they were unaware of the identity.

We believed the wreck would be situated several kilometers north of Dungun, to the north-east of Pulao Tengor, approximately one kilometer off shore. This is a popular spot for the fishermen to drop fish traps, and for spear fishing.

With the logistical assistance of local Tenngol Island dive operator, Charlie, we chartered a fishing boat and headed to the wreck site, with the objective of locating and identifying the Hatsutaka. Scheduled during one of South East Asia’s inter-monsoon periods, we coordinated the expedition to coincide with the best possible diving conditions. A large river estuary flows into the sea to the south of our target, but we would be diving sufficiently far north and up-current for visibility to remain unaffected.

Arriving early in the morning with near zero wave heights, we ran a brief sonar survey. Next, we deployed the shot line. Maximum depth in this area is relatively shallow at 35m, but on this day the north-south current was running exceptionally strong.

We planned five waves of dives throughout the day. Breaking into teams of two divers so we could discuss the observations from each dive and maximize the effectiveness of our survey. To our surprise, visibility was great, ranging upwards to 15m.

Diving the Hatsutaka

On the first dive our shot line was secured to what we believe to be the forward section of the wreck. The ship is broken into two main parts. The break occurs amidships, rear of the bridge.

The bow section is lying on its port side, measuring approximately 45m in length. This forward section lies on a roughly north-south orientation.

The stern section of the wreck is sitting upright on the seabed, approximately 25m off the bow section. It extends west, towards the mainland. The structure is still mostly solid, with portholes lining the hull. This is consistent with the information given in the original war report. The Hatsutaka was towed stern-first, breaking in two during the second attack.

In addition to the two main sections, there is scattering of wreckage in other areas. Primarily attributable to the original torpedo attack, people also speculate that it is a result of dynamite fishing. This has been ongoing until as recently as ten years ago when local marine police began enforcing a ban.

Artifacts

The wreck is rich with WW2 artifacts. In the debris field beneath the bridge, we observed typical WW2 Japanese naval items. Of particular interest was part of a pair of binoculars. They were very similar to a set recovered from the Japanese Heavy Cruiser. The cruisers name was the Haguro which sunk 55 miles southwest of Penang, Malaysia.

Also fascinating, was a large gyroscopic ship’s compass and range-finding instrument, fitted with intricate glass prisms and scales.

Scattered across the wreck we saw several pressure sensitive mechanisms. They had Japanese script stamped on them which we assumed to be part of depth charge triggers.

Many of the shells on the stern section had not exploded. We recovered an empty casing, measuring 40mm. Again this was consistent with the technical details for HIJMS Hatsutaka. We also observed what we determined to be an anti-aircraft turret mounting. We believe the gun had fallen off the mounting, into the wreckage.

This remains a very proud discovery for the team led by Tim Lawrence. He hopes to lead many more in the future bringing tech tech diving further forward in the local area.